Many popular applications in the world use some form of video streaming functionality. Implementing this feature can give you and your users a lot of creative power.

In this guide, we will cover how we can build a video streaming functionality using a simple Spring Boot application and a Javascript frontend.

We will also discuss what our client and server are doing behind the scenes to make this possible. Finally, as a bonus, we will see how we can write automated tests for our backend.

Prerequisites

To follow along with this tutorial, you need:

- The basics of Spring Framework (i.e. REST controllers, Hibernate and Spring Data JPA, and Lombok.

- An understanding of HTTP and RESTful web services.

- Some basic knowledge of Javascript fundamentals (i.e. fetch, using the DOM.

- An understanding of query parameters.

- Some knowledge on how to use your browser’s developer tools (specifically, inspecting the network information).

A high-level overview of the application

First, we need to understand and plan how the entire application will function.

In this section, we will discuss all the design specifications and inner workings of this application. This will include client-server interactions and functionality.

Design specifications

For this guide, our application will only implement video file uploads and video streaming capabilities.

From this foundation, you may add other essential features of a larger application such as authentication, authorization, a pretty UI, updating and deleting videos, etc.

Client-side architecture

For file upload, we’ll utilize a form whose fields will be saved on our server. For the video file, we’ll use an input field that accepts mp4 files and a text input field as the video name.

The data we send over will be regarded as multipart form data. You can read more about image file uploads here.

For those unaware, each field in the form is separated by a specific delimiter that is selected by the browser. In the case of a video file, it will be sent over as bytes.

To display saved videos, our frontend application will send a request to the server to retrieve all names of the videos on the database.

To play a specific video, we send another request to the server with the name of the video in the URL as a path variable.

In the UI, we’ll have a list of the names of all of the videos we saved each being a link. Each of these links will direct us back to the current page but with a query, parameter added specifying the video to play.

Finally, our frontend will send a request to the backend to retrieve the desired video based on the query parameter.

Note that we won’t be downloading the video in its entirety. Instead, we will be retrieving specific ranges of bytes based on how far the user has watched the video. This is the standard for video streaming. Downloading a video in its entirety can be time-consuming, especially for longer ones.

To do this, the browser will use a range header to tell our server what parts of the video to retrieve. Luckily, with an HTML video element, our browser will handle this automatically.

Server-side architecture

For the backend, we will set up the following REST endpoints to talk to our frontend:

/videoendpoint for posting videos./video/{name}endpoint where name is the name of the video to retrieve./video/allendpoint to get the names of all saved videos.

To keep things simple, users will have access to all videos. Therefore, we don’t need to create security systems. However, for a fully fleshed-out application, you should implement some form of authentication.

As for the lower-level details, we’ll have to consider what database to use and how we’ll read the range header to send the requested parts of a video.

For this simple application, it’s more convenient to use an H2 database that is easy to set up. Spring will thankfully do the heavy lifting for us.

Initializing the backend

To get started, navigate to the Spring Initializr. For the build tool, I prefer to use Maven.

For the language, we will be using Java 11, and for the packaging, we will select jar. When it comes to the dependencies, we need Spring Web, an h2 database, Spring Data JPA, and optionally but recommended, Lombok.

Creating our video entity and repository

Let’s create our Hibernate entity to represent saved video files:

package io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.domain;

import lombok.Data;

import lombok.NoArgsConstructor;

import javax.persistence.*;

@Entity

@Data

@NoArgsConstructor

public class Video{

@Id

@GeneratedValue(strategy = GenerationType.AUTO)

private Long id;

@Column(unique = true)

private String name;

@Lob

private byte[] data;

public Video(String name, byte[] data) {

this.name = name;

this.data = data;

}

}

Notice here that we have a data field of the type byte array, annotated with @Lob. This is how Hibernate will map the video byte data to a form readable using Java code.

The @Lob annotation simply means that when saved to the database, it will take on a type of BLOB (binary large object) in the database table.

From there, we can make our corresponding video repository:

package io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.repo;

import io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.domain.Video;

import org.springframework.data.jpa.repository.JpaRepository;

import org.springframework.data.jpa.repository.Query;

import org.springframework.stereotype.Repository;

import java.util.List;

@Repository

public interface VideoRepo extends JpaRepository<Video, Long> {

Video findByName(String name);

boolean existsByName(String name);

@Query(nativeQuery = true, value="SELECT name FROM video")

List<String> getAllEntryNames();

}

Here, we created a few custom abstract methods that suit the requirements of our application. Notably, the last method getAllEntryNames uses a native query (a query specific to the database we’re using) using the @Query annotation.

From the value field, you can see that we use our own SQL query to get the name column of our video table. With the magic of Spring Data JPA, these three methods will be implemented for us.

Creating and exposing our video service

From here, we can create a VideoService interface that will define how we access and use our Video entities:

package io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.services;

import io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.domain.Video;

import org.springframework.web.multipart.MultipartFile;

import java.io.IOException;

import java.util.List;

public interface VideoService {

Video getVideo(String name);

void saveVideo(MultipartFile file, String name) throws IOException;

List<String> getAllVideoNames();

}

Note that with Spring, it’s best practice to base your services on interfaces and inject beans of that generic interface instead of its implementations. This way, you have the flexibility to create environment-specific types of that interface and easily inject them throughout the application where appropriate.

Since you were injecting a bean as a generic interface you can quickly switch implementations based on the environment. This can also help if you need to deprecate a specific instance without breaking other code.

Then, our implementation of that interface should look as follows:

package io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.services;

import io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.domain.Video;

import io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.exceptions.VideoAlreadyExistsException;

import io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.exceptions.VideoNotFoundException;

import io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.repo.VideoRepo;

import lombok.AllArgsConstructor;

import org.springframework.stereotype.Service;

import org.springframework.web.multipart.MultipartFile;

import java.io.IOException;

import java.util.List;

@Service

@AllArgsConstructor

public class VideoServiceImpl implements VideoService {

private VideoRepo repo;

@Override

public Video getVideo(String name) {

if(!repo.existsByName(name)){

throw new VideoNotFoundException();

}

return repo.findByName(name);

}

@Override

public List<String> getAllVideoNames() {

return repo.getAllEntryNames();

}

@Override

public void saveVideo(MultipartFile file, String name) throws IOException {

if(repo.existsByName(name)){

throw new VideoAlreadyExistsException();

}

Video newVid = new Video(name, file.getBytes());

repo.save(newVid);

}

}

In the code above, we sometimes throw a VideoAlreadyExistsException which is a custom run-time exception defined as:

package io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.exceptions;

import org.springframework.http.HttpStatus;

import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.ResponseStatus;

@ResponseStatus(value = HttpStatus.CONFLICT, reason = "A video with this name already exists")

public class VideoAlreadyExistsException extends RuntimeException {

}

With the @ResponseStatus annotation, we specify the HTTP status code to send if this exception is thrown while handling a request.

We also specify with the reason parameter a message to send to the client in the end response. Note that for the client to see this message, we must set the following property in our application.properties file:

server.error.include-message=always

Finally, with the service finally created, we can build a simple controller to expose it:

package io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.controllers;

import io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.services.VideoService;

import lombok.AllArgsConstructor;

import org.springframework.core.io.ByteArrayResource;

import org.springframework.core.io.Resource;

import org.springframework.http.ResponseEntity;

import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.*;

import org.springframework.web.multipart.MultipartFile;

import java.io.IOException;

import java.util.List;

@RestController

@RequestMapping("video")

@AllArgsConstructor

public class VideoController {

private VideoService videoService;

// Each parameter annotated with @RequestParam corresponds to a form field where the String argument is the name of the field

@PostMapping()

public ResponseEntity<String> saveVideo(@RequestParam("file") MultipartFile file, @RequestParam("name") String name) throws IOException {

videoService.saveVideo(file, name);

return ResponseEntity.ok("Video saved successfully.");

}

// {name} is a path variable in the url. It is extracted as the String parameter annotated with @PathVariable

@GetMapping("{name}")

public ResponseEntity<Resource> getVideoByName(@PathVariable("name") String name){

return ResponseEntity

.ok(new ByteArrayResource(videoService.getVideo(name).getData()));

}

@GetMapping("all")

public ResponseEntity<List<String>> getAllVideoNames(){

return ResponseEntity

.ok(videoService.getAllVideoNames());

}

}

Code Update (August 2022)

At the time of writing this, a reader has brought to my attention that there were couple of problems here. For one, many video uploads would fail due to the file size limit being too small. We can fix this with the following config for our

application.propertiesfile:spring.servlet.multipart.max-file-size=50MB spring.servlet.multipart.max-request-size=50MBMoreover, we noticed that the video streaming didn’t work on Google chrome but it did on Firefox. Based on a console error, it seemed to be an issue with the content type being interpreted by the browser as JSON instead of bytes. To fix this, we need to update the

getVideoByNamemethod to explicitly state the content type:@GetMapping("{name}") public ResponseEntity<Resource> getVideoByName(@PathVariable("name") String name){ return ResponseEntity .status(HttpStatus.OK) .contentType(MediaType.APPLICATION_OCTET_STREAM) .body(new ByteArrayResource(videoService.getVideo(name).getData())); }Special thanks to Burak Tezcan for bringing this to my attention.

Building the client application

For our client application, we will have all the functionality on a single HTML file to make things simple.

This will include the form to save new videos, the video player, and the list of videos. The resulting HTML would look like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>JohnTube</title>

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0">

<link rel="stylesheet" href="styles.css">

</head>

<body>

<header>

<h1>JohnTube</h1>

</header>

<main>

<div id="video-list">

<header>

<h3>Your videos</h3>

</header>

<ul id="your-videos">

</ul>

</div>

<div id="video-player">

<header>

<h3 id="now-playing"></h3>

</header>

<video id="video-screen" width="720px" height="480px" controls></video>

</div>

<form id="video-form">

<fieldset>

<legend>Upload a video</legend>

<label for="file">Video File</label>

<input id="file" name="file" type="file" accept="application/mp4">

<label for="name">Video Name</label>

<input id="name" name="name" type="text">

<button type="submit">Save</button>

</fieldset>

</form>

</main>

<script src="main.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

The unordered list with id your-videos is left blank since we will be populating it dynamically using JavaScript.

Similarly, we keep the header with id now-playing blank, so we can set its contents based on the video being played.

Additionally, the video element will be left hidden unless the user specifies a video to watch via a query parameter. The CSS for this would look like so:

#video-player{

display: none;

}

#video-form{

width: 60%;

}

As for the JavaScript, let’s start by retrieving the necessary DOM elements to manipulate:

const form = document.querySelector('#video-form');

const videoDiv = document.querySelector('#video-player');

const videoScreen = document.querySelector('#video-screen');

Alongside that, we’ll need to retrieve an object to access our query parameters:

const queryParams = Object.fromEntries(new URLSearchParams(window.location.search));

With the above object, we simply access any query parameters as properties of said object. For instance, if we had a URL like http://localhost:4200/video-sharing-app/index.html?video=myVid, we can access the video query parameter as: queryParams.video.

From there, let’s start populating the list of saved videos:

fetch('http://localhost:8080/video/all')

.then(result => result.json())

.then(result => {

const myVids = document.querySelector('#your-videos');

if(result.length > 0){

for(let vid of result){

const li = document.createElement('LI');

const link = document.createElement('A');

link.innerText = vid;

link.href = window.location.origin + window.location.pathname + '?video=' + vid;

li.appendChild(link);

myVids.appendChild(li);

}

}else{

myVids.innerHTML = 'No videos found';

}

});

In the above code, we send a GET request to our server at http://localhost:8080/video/all using fetch.

The resulting JSON response is an array of strings of the names of the videos we saved. For each of these strings, we make li elements containing links to the current page.

For each of these links, we append a video query parameter whose value is the corresponding string in the array. If the array is empty, we add a message in our list indicating that no videos were found.

Now that we have a way to display all videos and links to play them, let’s implement the functionality of playing these videos:

if(queryParams.video){

videoScreen.src = `http://localhost:8080/video/${queryParams.video}`;

videoDiv.style.display = 'block';

document.querySelector('#now-playing')

.innerText = 'Now playing ' + queryParams.video;

}

First, we check if the video query parameter exists. If so, we set the src attribute of the video element to be the URL to retrieve it from the backend.

From there, we make the video player visible and add a title indicating what video is being played.

Lastly, we need to make the form send a request to save a video to our backend. The code to do this is as follows:

form.addEventListener('submit', ev => {

ev.preventDefault();

let data = new FormData(form);

fetch('http://localhost:8080/video', {

method: 'POST',

body: data

}).then(result => result.text()).then(_ => {

window.location.reload();

});

});

Here, we add an event listener that will be invoked when we submit our form. We first need to prevent the default submission behavior to ensure our planned activity works.

Then, we create a new FormData object to send as our request body. Finally, once the response comes back, we refresh the page to allow our app to show a new list of videos.

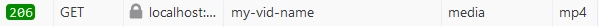

Now that we have the application created, open the network tab in your dev tools to monitor requests to our backend. Try saving a new video and clicking the link to play it. You should see something like this:

Notice the 206 status code. A quick Google search will tell you this means our request is for partial content.

As discussed, the browser automatically sends a request for only parts of the video we are looking to play. Upon further inspection, you can also find the range header I talked about:

The above line specifies that we are asking for the very beginning of the video when we sent this request.

Thankfully for us, Spring handled sending the chunks of bytes over for us so we didn’t have to worry about those low-level details.

If you want to observe this further, you can extract the range header in our backend using the @RequestHeader annotation.

Writing unit tests for our backend

As a bonus, let’s write some unit tests for our application. It’s nice to know how to write tests for your applications to identify and remove bugs.

Writing tests makes it easier to quickly validate your code to ensure you don’t accidentally break things in the future.

With Spring, we will be using JUnit and Mockito to help us write our tests. In case you don’t know how to use these tools, I have a guide on how to use them here.

Unit testing our video service

Note that we’ll only write tests for our VideoServiceImpl class.

In our /src/test/java folder, create a VideoServiceImplTest class and initialize it as follows:

package io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.services;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test;

class VideoServiceImplTest {

@Test

void getVideo() {

}

@Test

void getAllVideoNames() {

}

@Test

void saveVideo() {

}

}

Since we are writing unit tests for this class, we should use mocks for any classes that it relies on. This allows us to know that if an error occurs it is because of the VideoServiceImpl class and not another class that it utilizes.

We ensure this by hard coding the correct behavior in our mocks. In our case, we will have to create a mock for the VideoRepo interface that our class uses:

package io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.services;

import io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.domain.Video;

import io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.repo.VideoRepo;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test;

import org.springframework.web.multipart.MultipartFile;

/*

Import all the static methods in the Mockito class so we can use them as though they are methods in this class.

These include methods such as mock, when, etc. Same with the JUnit assertions.

*/

import java.io.IOException;

import java.util.List;

import static org.mockito.Mockito.*;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.*;

class VideoServiceImplTest {

VideoRepo repo = mock(VideoRepo.class);

VideoService service = new VideoServiceImpl(repo);

// Test value for our tests

String testName = "myVid";

// Empty tests go here…

}

From there, let’s write a test for retrieving videos:

@Test

void getVideo() {

Video expected = new Video(testName, null);

// When our VideoService object calls repo.findByName(testName), return expected

when(repo.findByName(testName))

.thenReturn(expected);

// When our VideoService object calls repo.existsByName(testName), return true

when(repo.existsByName(testName))

.thenReturn(true);

Video actual = service.getVideo(testName);

assertEquals(expected, actual);

verify(repo, times(1)).existsByName(testName);

verify(repo, times(1)).findByName(testName);

}

Here, we hard-coded the behavior of our mock using Mockito’s when method. So we know the VideoRepo class our VideoService is using is working appropriately.

We then check that the VideoService object correctly returns the video retrieved from our repository.

Finally, we confirm using Mockito’s verify method that the class calls the existsByName and findByName methods once.

Similarly, we can also write simple tests for the other methods of this class:

@Test

void getAllVideoNames() {

List<String> expected = List.of("myVid", "otherVid");

when(repo.getAllEntryNames())

.thenReturn(expected);

List<String> actual = service.getAllVideoNames();

assertEquals(expected, actual);

verify(repo, times(1)).getAllEntryNames();

}

@Test

void saveVideo() throws IOException {

MultipartFile file = mock(MultipartFile.class);

Video testVid = new Video(testName, file.getBytes());

service.saveVideo(file, testName);

verify(repo, times(1)).existsByName(testName);

verify(repo, times(1)).save(testVid);

}

Writing integration tests for our backend

Now, let’s see how we can write integration tests for that same service. Unlike unit tests, integration tests check the interaction between different components together.

As such, we won’t be using mocks for our dependencies and instead will be bringing up the Spring context to inject the actual beans.

For this case, I will be mocking a MultipartFile so we may easily have an instance to pass to a method that we are testing.

Integration testing our video service

To Bring up the Spring context for our test class, we need to add the @SpringBootTest annotation on the class level.

Additionally, we will be adding the @Transactional annotation which will, in this context, roll back any database operations after a test is executed.

This way, database interactions that occur in one test won’t interfere with another since the database will be cleared before each test.

From there, we can inject Spring beans into our class as normal and create a simple testName field which we will use in our tests:

@Autowired

VideoService service;

@Autowired

VideoRepo repo;

String testName = "myVid";

With that, creating our tests should be fairly simple:

package io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.services;

import io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.domain.Video;

import io.john.amiscaray.videosharingdemo.repo.VideoRepo;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test;

import org.springframework.beans.factory.annotation.Autowired;

import org.springframework.boot.test.context.SpringBootTest;

import org.springframework.web.multipart.MultipartFile;

import javax.transaction.Transactional;

import java.io.IOException;

import java.util.List;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.*;

import static org.mockito.Mockito.*;

@SpringBootTest

@Transactional

public class VideoServiceImplIT {

@Autowired

VideoService service;

@Autowired

VideoRepo repo;

String testName = "myVid";

@Test

void getVideo() {

Video expected = new Video(testName, null);

repo.save(expected);

Video actual = service.getVideo(testName);

// The result from service.getVideo(testName) should be expected Video instance above

assertEquals(expected, actual);

}

@Test

void saveVideo() throws IOException {

MultipartFile file = mock(MultipartFile.class);

service.saveVideo(file, testName);

// After saving the video using the service, the repository should say that the video exists

assertTrue(repo.existsByName(testName));

}

@Test

void getAllVideoNames() {

List<String> expected = List.of(testName);

repo.save(new Video(testName, null));

List<String> actual = service.getAllVideoNames();

// Check the service returns a list of the same contents as the expected list of videos

assertTrue(expected.size() == actual.size() && expected.containsAll(actual) && actual.containsAll(expected));

}

}

Conclusion

With that, we have discussed how you would develop a full-stack video streaming application with our chosen tech stack.

We also talked about how to upload video files to a database, how to retrieve and play our saved videos, and as a helpful bonus, how we can write tests for our backend.

As a further exercise and a potential project, I encourage you to try to build onto the code we wrote in this tutorial.

Happy Coding!

Comments: